The Tarot of Ideals

The Trump Cards

The Tarot was born in medieval Italy (or possibly France) when 21 trump cards (and a wild card) were added to the standard deck of four suits. Paul Huson has done a great deal of research into the origin of the trumps as imagery from the pageant carts that were drawn through the streets as part of mystery, miracle, and morality plays of the time, especially The Dance of Death. These carts were called Trionfi, or Triumphs, which is the origin of the word trump. See also The Tarot by Robert Place for a wealth of historic background to the trump and court cards.

Below are thumbnail sketches of each trump card from the perspective of history. The goal of studying their origin like this is to get inside the mind of the people who actually created them, which is the starting point for understanding their meaning. (Which is not to say that they cannot then be adapted to the modern world.) I have made an occasional reference to the images if it helps to elucidate the original intent. But the goal is not to “microinterpret” the images, or in the final analysis, to rely on them at all.

Because of their nature as spiritual or timeless archetypes, and because they literally trump the minor suit cards, the trump cards are generally seen as having a deeper significance than the former. They are, after all, what characterize the Tarot.

|

The Magician Alternately, the Juggler. A street magician, carnival entertainer, huckster; his “magic” is sleight-of-hand. A skillful and charismatic performer who has the ability to awe the crowds, but also to fleece the unwary. (The hand really is quicker than the eye.) Allegorically, a miracle worker. Sometimes a part of the Dance of Death with the rest, but may also have been a sideshow to the pageant that follows. Most see the suits represented in the cups, balls/coins, and knives on the table, and the wand that the Magician holds. (The only thing missing is—a deck of cards!) |

|

The Papesse Perhaps the most unusual card from a historical standpoint, she may represent one of several actual people. According to the legend of Pope Joan, a learned ninth-century woman disguised herself as a man and was eventually elected pope. And in 1300, a sect called the Guglielmites elected Sister Manfreda, a member of the Visconti family, as their pope. Of note, one of the earliest Tarot decks was made for the Visconti-Sforza family, and their Papesse wears a nun’s habit. On the other hand, some later decks replaced the Pope and Papesse with Jupiter and Juno (spelled Junon); the latter may be an intentional substitute for “Johanna,” Joan. To top it all off, Huson points out that dozens of German miracle plays featured Pope Joan. Here is another theory. In the decades leading up to the creation of the Tarot, the church had been divided by the Western Schism, during which two or three people claimed to be pope. It began in 1378 when Clement VII, now considered an antipope, was elected by French cardinals in defiance of pope Urban VI and took up residence in Avignon, France. One of Clement’s main allies, who conspired with him against his enemies and gave him financial support, was the controversial Queen of Naples. Urban declared her a heretic, and St. Catherine of Siena accused her of being a servant of the devil. She was likely assassinated in 1382 for her efforts, and her body was thrown into a well. And her name was—Joan. To top it all off, Joan had sold Avignon to Pope Clement VI in 1348. Does the Tarot deck facetiously refer to Queen Joan as the “Papesse”? Of note, Avignon, in southeastern France, is about 60 miles north of Marseilles, and 350 miles west of Milan, home of the Visconti family. So the Papesse represents spiritual influence or example of a “cups” nature like the Queen; or more generally, one’s inner spiritual experience. But she is unconventional, a usurper in the eyes of orthodoxy. One of her historical referents represented an “underground” movement; another kept a very deep secret. Joan achieved her position through her great learning, and the old decks depict her holding a book. Today sometimes called the High Priestess to generalize the role beyond the modern Catholic church. |

|

The Empress Female or maternal secular authority like the Queen, but of an all-encompassing nature as befitting her position as a trump card and as the wife of the Emperor. As ancient rulers were sometimes deified, the Empress may be considered something of an earth goddess, a supreme mother figure, the embodiment of all things female. |

|

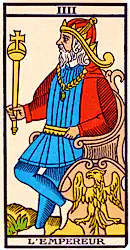

The Emperor The Holy Roman Emperor; note the eagle on the shields. Male or paternal secular authority of a “rods” nature like the King. Possibly the embodiment of male deity, a supreme father. (Although in reality, the Holy Roman Emperor was elected and ruled over a patchwork of semi-autonomous states.) How do the Emperor and Empress differ from the Kings and Queens? First of all, there are four Kings and Queens, each associated with an individual suit, implying that they are the monarchs of specific domains. An emperor may rule over a number of kings, who retain their position in exchange for loyalty to the empire. The Emperor and Empress cards, by virtue of this concept, and the fact that they number among the trumps, represent universal, “cosmic” secular authority. In addition, the Kings and Queens may represent actual people in the current situation; the Emperor and Empress, like the other trumps, are more abstract concepts. |

|

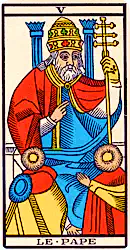

The Pope In medieval Italy, universally recognizable as the ultimate spiritual authority on earth. He clearly represents orthodoxy, the external expression of religious activity. As he was the one who crowned the emperor, his authority was in theory greater; but in reality, popes and emperors clashed, sometimes dramatically, during the middle ages and renaissance. And for several decades prior to the creation of the Tarot, there were even rival popes. Today the card is sometimes called the High Priest to generalize the role beyond the modern Catholic church; but this obscures the fact that the original name means “father.” (The word hierophant means “displayer of the holy” and was the title of the chief priest of the ancient Eleusinian mysteries.) |

|

The Lovers Originally, just Love, without much hint of allegory. The lovers were soon joined by a clergyman performing a wedding ceremony; the scene later morphed into a man having to choose between two women, presumably representing virtue and sensuality. Or is the older woman the man’s mother? Love can be as complicated as you want it to be . . . . The idea of the card representing a decision comes from these later developments. |

|

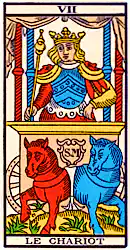

The Chariot The classical Roman triumph was a victory parade in which a military commander (like our “grand marshal”) rode a chariot through the streets. Little wonder that a set of cards representing triumphs includes a chariot. Another old name for the card was The Reward of Victory. Its presence following the previous card suggests the familiar themes of love and war. |

|

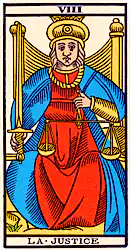

Justice One of Plato’s four cardinal virtues (along with fortitude, temperance, and prudence), Justice refers to interpersonal justice or fairness. The Greek concept also included observance of the social order. The law enforcement type of justice is an extension of the concept. |

|

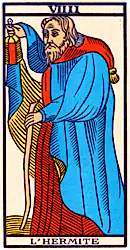

The Hermit The oldest Tarot cards depict an old man carrying an hourglass, not a lantern, implying that he is Father Time. Other old captions include Time, or just The Old Man. A hermit carrying a lantern calls to mind Diogenes, the Greek philosopher who lived in a barrel and went about searching for an honest man. To reconcile these two images, one might think of the Hermit as a wizened sage who embodies both the wisdom and the ravages of time. Remember, time is always running out. |

|

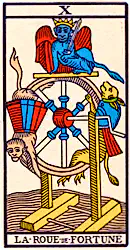

The Wheel of Fortune Fortuna was the Roman goddess of luck and/or fate, and her will has been depicted as a cycle, or wheel, since ancient times. You may get to the top of the wheel, but you can only stay there until it turns again. Fortune herself is sometimes depicted as blindfolded. In discussing this card, both Paul Huson and Tom Tadfor Little were moved to quote from the thirteenth-century Carmina Burana, whose opening title, Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World) consists of the names of three Tarot cards. |

|

Fortitude The second of the cardinal virtues included in the standard Tarot deck, Fortitude refers to courage or moral strength. The courage to put one’s hands into a lion’s mouth, not the physical strength to hold it open. It also includes the ideas of endurance or forbearance. |

|

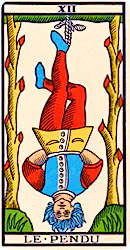

The Hanged Man Alternately, the Traitor. The discordance between the modern romanticized interpretation of this card, and what it actually represents, is beyond my understanding. To be hanged up by the feet like this was a humiliating medieval punishment. While still alive, it would be the equivalent of being pilloried, or even crucified if the end was death. (And imagine how much harder it would be on your joints to be hung by just one leg. For a couple of days.) In modern times, Mussolini was publicly hanged by his feet after being summarily executed, and his disfigured body was stoned by the crowd. In a traitor’s absence, “shame paintings” depicting him suspended like this were sometimes publicly displayed. Of course, one side’s traitor may be the other side’s patriot, and the card may be interpreted as martyrdom or sacrifice, to which the victim may have submitted himself willingly on some level. But the scene is still one of disgrace and abuse, not some sort of peaceful upside-down yoga meditation. |

|

Death The end of this life; the beginning of the next may be implied but is not stated. It is easy to interpret this card as one of life’s many transitions; but in the Dance of Death morality play from which much of the Tarot imagery is drawn, the transition was clearly the big one out of this life and into the hereafter. Old superstitious decks don’t even caption this card; it is clearly a grim reaper type of figure. And it is number thirteen. A central theme of the morality plays was that death comes for all regardless of their station, including lovers, hermits, popes, and emperors. “I am Death, that dreads no man,” quotes Huson from the play Everyman. Death is the dark side of a transition, the end, inevitable and irrevocable. |

|

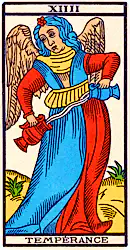

Temperance The last of the Tarot’s cardinal virtues. (The absence of prudence has been variously interpreted). As moderation or avoidance of excess, traditional imagery includes the diluting (not replacing) of wine with water. |

|

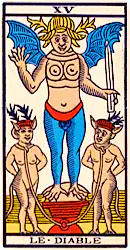

The Devil The Devil tempts, enslaves, and torments, but will have his own reckoning. The medieval devil is always depicted as grotesque, not a cute little imp (unlike, perhaps, his minions) or a halloween costume, and definitely not any sort of romanticized vision of untamed nature. Slavery, torture, and genocide are just plain ugly. |

|

The House of God Alternately, the Tower. An older name name seems to have been The House of the Devil. The latter is consistent with the dramatically-staged mystery play about the harrowing of hell, or the rescue of righteous souls from limbo. It also fits into a series about the afterlife that began with The Hanged Man, Death, and The Devil, and is followed by Judgment. Evil is being vanquished, the proud struck down, the fortifications breached, and the righteous set free. |

|

The Star As we near the end of the trump series we encounter three heavenly bodies of increasing brilliance. It seems appropriate, now that we have passed through Death and limbo, and approach Judgment and (it is hoped) heaven. A star is a remote but steady guidepost or sign, one that orients us in the dark. Stars have long represented wishes or hopes. They are the reference points for everything else, including the moon and sun. And the planets (wandering stars) follow complex and age-old paths through the cosmos. The traditional cards are full of allegory; the imagery on the Star card may suggest Aquarius the water bearer, or the star of Bethlehem, or the morning or evening star. |

|

The Moon The moon is the feminine, mysterious, waxing and waning light of the night. She comes and goes in a tireless monthly cycle of renewal. She is associated with sleep and dreams, water and tides, madness, and activities that shrink from the light of day. The yin of water and earth. Two dogs are baying in the background, consistent with the mood of the nighttime scene. The crustacean is included because the moon was associated with the constellation Cancer, the crab. Note also the general theme of influence over animals, as opposed to a natural element (water) with the star, and humans with the sun. |

|

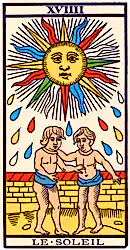

The Sun The sun is the constant, brilliant, and life-giving light of day. Consciousness and visibility as opposed to the unconscious and mystery; the yang of fire and air. Often associated with warmth and happiness, but also blinding and scorching in excess. The solstices and equinoxes have long been observed and celebrated as markers for the cycle of planting and harvest. The children may represent Gemini the twins, giving each of the heavenly body cards an associated constellation; or they could suggest creativity and energy. |

|

Judgment As in the last judgment, the day of reckoning, payback, karma. Alternately, the Angel, blowing a trumpet and summoning the dead to rise. Most cards actually depict the resurrection, which would be the “other side” of the Death card. |

|

The World The title of this card is a little curious; one might expect something like “Heaven.” It evidently represents the Earth of the apocalyptic “a new heaven and a new Earth.” The central character is in fact surrounded by four apocalyptic creatures. Another title for the card was Anima Mundi, The Soul of the World. A transformed, perfected world, a new creation or beginning. |

The Wild Card

|

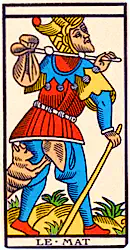

The Fool Alternately, the Madman. Not a numbered trump card, but a wild card like the joker of modern decks. Originally pictured as something like a homeless mentally ill person, he later took on the costume of a jester, and may have played a similar role in the triumph pageants. An eccentric wanderer, clearly outside mainstream society. Someone who can speak the truth and get away with it. Often idealized as innocent and carefree. |